Towards the end of last year, we put a call out to Axiell experts asking what they saw as the big trends for libraries, museums, archives and more in 2019 and beyond. In this article, we have gathered these insights, exploring what emerging technology means for the future of culture. We’ll also look at some of the exciting work that is already taking place and how technology is being used to support the core goals of the industry.

From Working ‘For’ the Community to Working ‘With’ the Community

With budgets consistently under pressure, most cultural institutions rely to some extent on community groups, volunteers or groups of researchers and enthusiasts in order to fulfil their mission. However, the value of this extends far beyond making savings on staffing costs.

At Library 10 in Helsinki, 90% of events held at the public library are organised by the community, helping build a collaborative space that people want to share and use.

Whilst crowdsourcing is becoming an increasingly popular way for museums to tap into communities of experts for cataloguing and tagging records. Examples of this were discussed in our Online Collections Expert Discussion Panel, including meetups held by the Rijksmuseum, where bird enthusiasts were brought in to identify and tag bird species in paintings; with similar activities also undertaken by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Is it a bird? Is it a plane? Ask the experts.

The community is still, however, a relatively untapped resource. People go to libraries, museums or archives to learn, but rarely are the stories and knowledge uncovered captured by the institutions themselves.

Creating Interactive and Interpretive Experiences

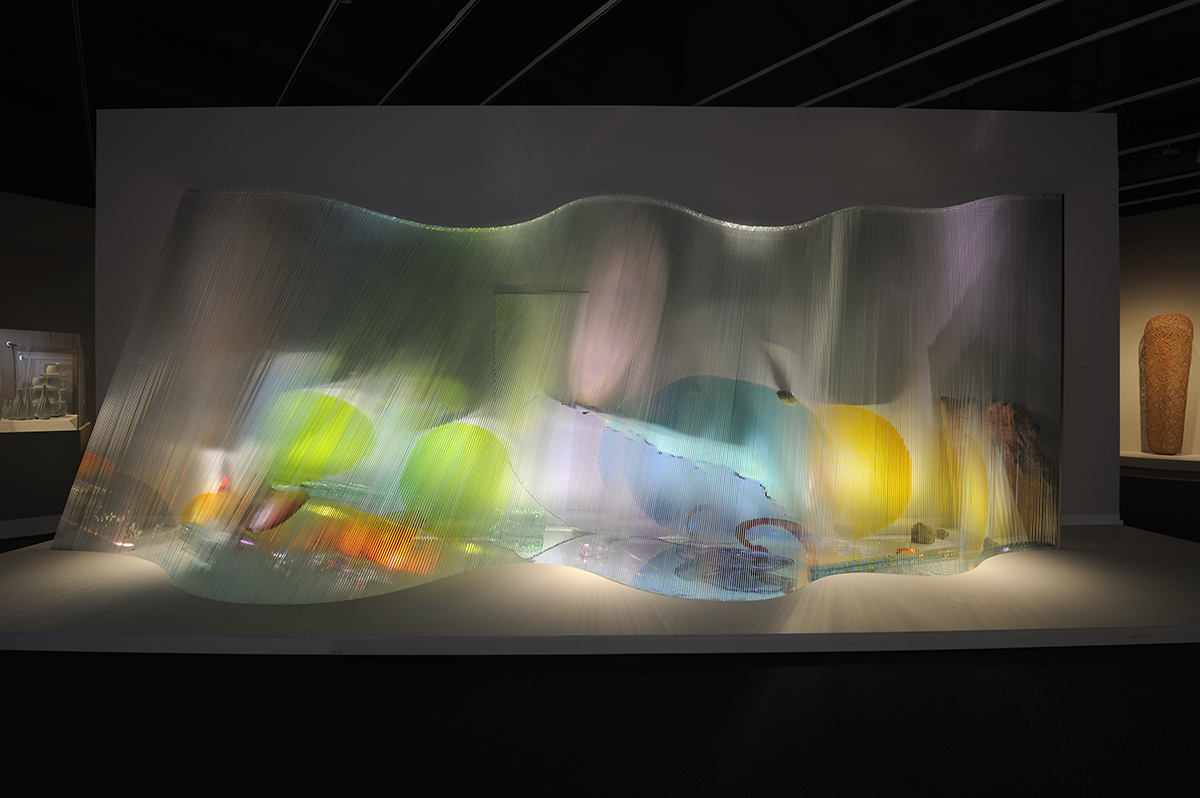

Experience. A single word that has changed so much. It seems that no longer is simply putting art, artefacts and books out on display enough. Now, museums and galleries are providing ways for visitors to interact with objects, to open them up and personalise them.

The Museum of Photographic Arts’ 7 Billion Others exhibition used a camera to recreate visitors’ faces on a screen, creating a mosaic from the thousands of people from around the world that they had interviewed. This is art that comes to life, creating a new layer upon that which already exists.

According to David Newbury of the Getty, exhibitions like this present a philosophical conundrum for cultural institutions as they shift from curators to creators. Whereas libraries have for a long time been very active in this regard, providing writing workshops and even self-publishing.

But there’s more to buzzwords like ‘experience’, ‘interactivity’ and ‘engagement’ than just new ways of interpreting art. There’s a greater recognition of the visitor as an active participant in the art or in the storytelling. This user-centred approach will help libraries, galleries and museums grow with their audience, and will help their audience grow to live more culturally enriched lives.

VR in Culture: Will Virtual Become the Reality?

When it comes to tech, it doesn’t get much more interactive than virtual reality. Climb Machu Picchu, visit Pompeii or the Babylonic gardens or stroll through the halls of the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum virtually. The technology might help us burn less aeroplane fuel and protect heavily tourist-trodden wonders, it might provide an admission ticket for those with difficulties getting about, and it might also be a lifeline.

VR is increasingly being used to help dementia sufferers tap into emotional recall. Some libraries already run ‚Reminiscence‘ sessions using local history collections, to help those with dementia trigger memories and regain connections to the present. It is hoped VR can go further. Public Libraries Online suggests library staff could tailor experiences for recipients, helping them revisit experiences, such as past trips to distant cities using Google Streetview, or museums and art galleries using the ever-growing number of virtual tours on offer.

Virtual reality is also providing new, more immersive ways of telling stories and presenting objects and knowledge from the collection. The National Museum of Finland allowed people to feel as though they were stepping inside a painting, whilst The Tate Modern took visitors inside Modigliani’s Paris studio. View more projects here.

AI in the Cultural Sector

Machine learning and “reasoning” has huge potential to help people access relevant information faster. For the cultural industry, this means even greater competition in the information space. But also new opportunities.

The promise is that connecting data from our collections and catalogues will help us build a new map of human knowledge, discover new truths and become a more informed and enriched society.

In our Online Collections Discussion Panel, experts discussed how AI could help speed up the cataloguing and digitisation of collections by doing some of the ‘boring stuff’. The AI might be able to describe what’s in an image, what colour it is or what a passage of text says.

In fact, AI is already being used to recognise art style and objects, mine the Vatican’s archives, and provide personalised experiences via facial recognition. You can read more examples here.

Yet, a post on IFLA’s blog makes the point that AI is prone to inherent bias and discrimination, since it is merely making use of the data available to it. Therefore, the role of librarians, information professionals and cultural institutions in helping people find reliable information becomes even more important. As information becomes easier to access, so must our tools be sharper to discern fact from fiction.

Voice Command

Voice command has the potential to make life easier for both staff and visitors in cultural institutions.

Commands may be used to make staff’s daily work routine simpler and faster: “Show me the metadata (for this object)”, “Discard (this object)”, “Show me N.N. (patron record)”. This may be incredibly useful for staff working with their hands, on the go or to open up roles for those that require enhanced accessibility.

The technology may also support libraries, museums, archives and other institutions in their mission to make knowledge and culture accessible to all. The Museums of Modern Art in New York is aiming to improve engagement and navigation around the museum collection for users, by integrating the Amazon Echo with their collections database. This will be particularly useful to those with visual impairment.

Less Intrusive Tech

The purpose of technology should always be to make tasks or life in general easier for us, yet so often it seems like just another barrier. That is why some airports are thinking of using the facial recognition software already used at border control to let passengers check in, get through security and board, unimpeded.

Karen Wong, Senior Developer at Axiell asks “Is it time technology fades into the background?”

The same should be true of the software used across the cultural sector. Technology should help staff spend more time on higher value tasks (as we hear so often from public libraries), which may include education programmes, outreach or engaging more with users. This may mean that staff need to refocus on soft skills, with jobs requiring high levels of social skills growing 12% in the US between 1980 and 2012, according to The Wall Street Journal.

In our product management team, we say “If our software is used less but is more useful then we will enable our customers to succeed.”

Balancing Security and Openness

The belief within the cultural sector that information and data should be open and shareable is nothing new. With technology making this more and more of a possibility, the balancing act between openness and security is one of the industry’s defining debates.

Opening up collection data to the public and to other organisations provides the opportunity for crowdsourcing and making new discoveries through shared expertise. However, the number one priority for institutions and suppliers must always be security. The more data that is opened up and shared, the higher the threat of hacking. APIs will likely play an increasing role in providing that secure bridge between systems.

Personal data may also be shared between organisations. The UK authority of Cambridgeshire is trialling a ‘Culture Card’ that tracks young people’s engagement with cultural venues. The aim is to improve engagement among those from disadvantaged backgrounds and plug gaps in knowledge of how culture impacts education and skills.

GDPR provides clearer guidance on protecting personal data for institutions in the EU (or interacting with those in the EU), but also severe financial consequences for those in breach.

There will also be increasing calls for transparency among the big tech players. It important that we know how our data is being used and that it is safe.

Avoid Jumping On the Latest ‘Shiny Thing’

There is a great risk with new technologies of jumping on the bandwagon and throwing huge sums of money at a fad with no real longevity or value. One thing the experts agree on is that your goals must drive the technology, rather than the other way around.

Still, the cultural industry must evolve. People’s habits are changing, and the way people interact with content and with institutions is changing. From this, a new ethos is starting to take hold within the industry: meet people where they are. If people want to interact online, you must be online. If people walk around the gallery staring more at their phone than at the exhibits, you must reach them there. If people are housebound and can’t go to the museum, take the museum to them.